Dissertation

Tango Chirimen and Te-Nassen

As kimono and furoshiki started disappearing from everyday life, chirimen too started to vanish. All the same, the techniques used in its creation are exclusively unique to Japan. And so, creators of chirimen are now considering how to reapply these techniques, fostered and cultivated over many centuries, to the modern day and how to apply new materials and methods to develop and create a new history for chirimen.

| Category: | Material |

|---|

| Date: | 2022.07.27 |

|---|

| Tags: | #tangochirimen #tenassen #visvim |

|---|

Weaving and Dyeing, reinterpreting lost techniques to produce new products.

Tango chirimen is a type of silk crepe originating in the coastal Tango region of northern Kyoto Prefecture that has been produced for around 300 years. Chirimen (literally "shrunken surface") fabric is created by using untwisted raw silk threads for the warp and strongly twisted silk threads for the weft. When the fabric is refined (a process known as "seiren"), the twisted threads try to untwist, and this movement creates small creases (known as "shibo") on the surface of the fabric. This property means that long-fibered raw silk threads suitable for strong twisting is used. Tango chirimen has been valued as a luxury textile for centuries for the profound crimped texture of the silk, its soft touch, and its crease-resistant elasticity.

Tango's history of producing silken goods stretches back 1300 years, but it was only in the past few hundred years that chirimen started to be produced. It was in 1720 when a silk merchant called Saheiji (later changed his name to Morita Jirobe) who moved from his home in Mineyamacho to enter into service at a weaver in Nishijin, Kyoto. There, he studied how to create chirimen and brought that knowledge back with him to Tango. The techniques and production of chirimen spread across the entire region, bringing a period of prosperity from the end of the Edo period right up to the beginning of the Showa era.

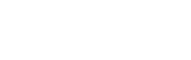

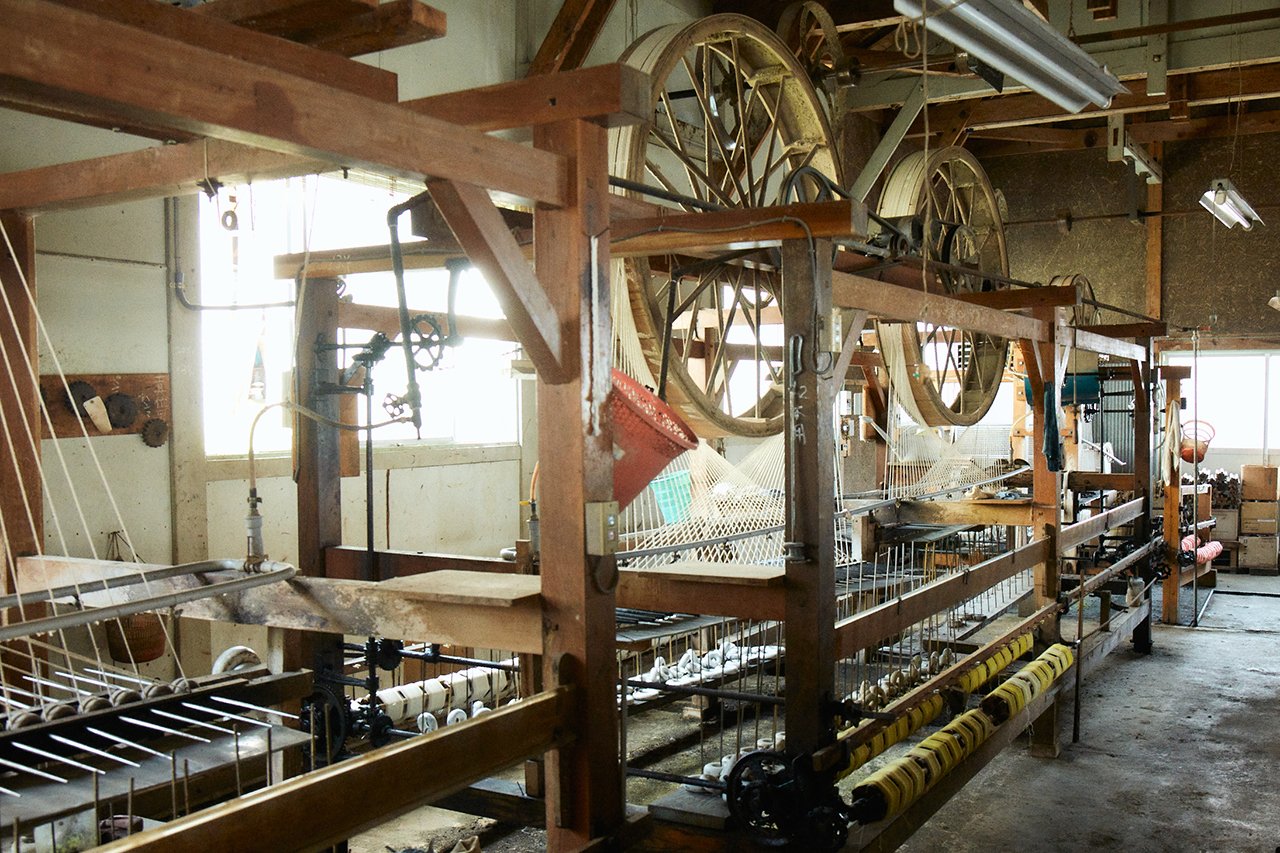

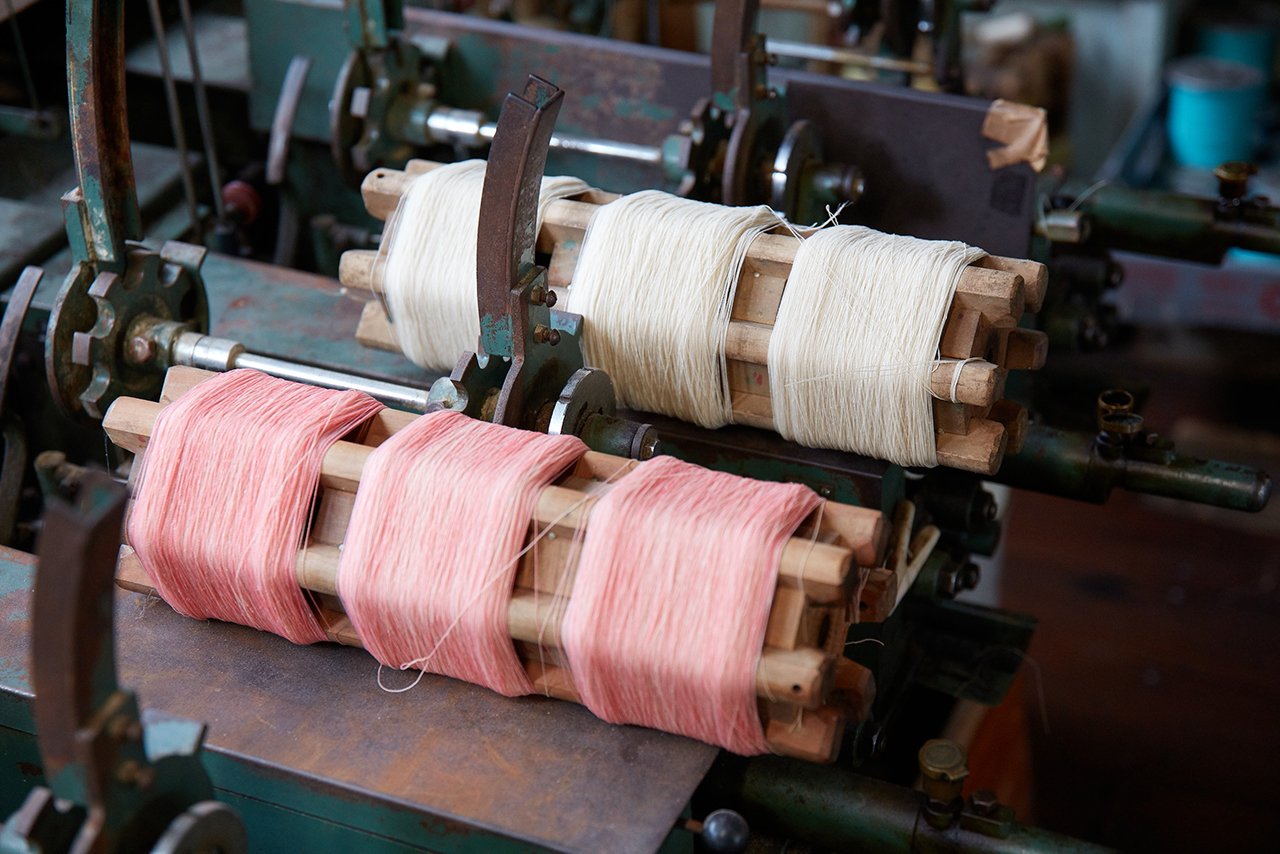

In Yosano of Yosa District in Kyoto, there is a street that is known as Chirimen Road which has preserved the essence of the chirimen workshop-filled town of the past. It is in this town, once filled with the clattering sound of workshops, where Yamato Orimono, established in 1833, continues to produce chirimen. Inside the workshop, which was shown to us by the sixth-generation head, Keiichi Yamazoe, is a whole line of hatcho-nenshiki--a type of yarn twisting machine which twists the threads required for chirimen. This machine which uses momentum to twist multiple threads at once was invented in the Edo period and was a widely used and crucial part of chirimen production until the middle of the Meiji era. Yamato Orimono's machines are still in perfect working order.

A number of steps are required to produce Tango chirimen, beginning with goshi, where the raw silk thread is bundled to reach the required thickness to be used in weaving, then yoko-taki, where the thread is cooked in an iron kettle to soften it, then shitakuda-maki, where the thread is wrapped around tubes in order to be used in the hatcho yarn twisting machine, then the threads are twisted, and finally the weaving process is conducted where the strongly twisted threads are woven together with the other thread. A bundle of 3 to 30 threads is generally used in goshi, and an average of around 16 threads is used for thicker kimono material.

The hatcho yarn twisting machine is fitted with the tubes prepared during shitakuda-maki, and its large wooden wheel is spun. The ropes connected to the wooden wheel drives kinetic energy into koma--circular pieces of wood that the thread is also attached to--which spin and cause the thread to twist. During this process, porcelain weights known as shizuwa are attached, which provide tensile strength to make sure the thread is twisted uniformly. The number of times the thread is twisted is affected by the weight of the shizuwa, the number of times the koma spin, and the amount of thread being fed in. For every meter of thread, the thread can be twisted from 1,500 up to 4,000 times. It is a testament to the craftspeople's experience and skill that they can finely control the thickness of the thread, the springiness of the fabric, its feel and its texture all by making fine adjustments to every one of these complicated elements.

When the threads are twisted too much, the fibers are prone to snapping, so the threads must constantly be kept damp. For thicker threads, the spinning process can take dozens of hours, but during this time, the craftspeople need to constantly check that the threads remain unbroken and make adjustments and repairs as necessary. There is a long history of using cherry wood which has been dried out for a period of at least five years to make the bobbins which wind and collect the threads. The wound silk thread shrinks in size when dry, causing it to bite into the wood. This characteristic means that other materials such as metal would increase the risk of the threads snapping, making the cherry wood an irreplaceable part of the process.

When weaving, usually two left-twisted weft threads and two right-twisted warp threads are alternately woven and variations in the crimps can be created by interweaving one or three threads instead. Hitokoshi chirimen is a style of chirimen where the left-twisted threads and right-twisted threads are alternated every time they cross over the warp which results in a fine crimping and soft texture. A whole variety of different chirimen has been developed resulting in a wide range of textures.

Tango chirimen had spread across the whole of Japan with such a high demand for kimono in the early Showa era and for furoshiki cloths after WWII that it was thought every piece of chirimen that was woven would be sold. However, following the post-war economic boom in Japan and changes in lifestyle of the Japanese people, the demand for chirimen dropped significantly. Whereas around 9.9 million rolls of fabric for kimonos were being produced annually in the middle of the 1970s, present day production has dropped to approximately 17,000 rolls.

As kimono and furoshiki started disappearing from everyday life, chirimen too started to vanish. All the same, the techniques used in its creation are exclusively unique to Japan. And so, creators of chirimen are now considering how to reapply these techniques, fostered and cultivated over many centuries, to the modern day and how to apply new materials and methods to develop and create a new history for chirimen. One of the techniques that has been devised is shrink proofing, a method which is able to overcome the shortcoming wherein the chirimen is more prone to shrinking and losing its distinctive springy texture when it gets wet. This technique has been applied to visvim shirts made of chirimen, creating articles of clothing that are suitable for washing at home.

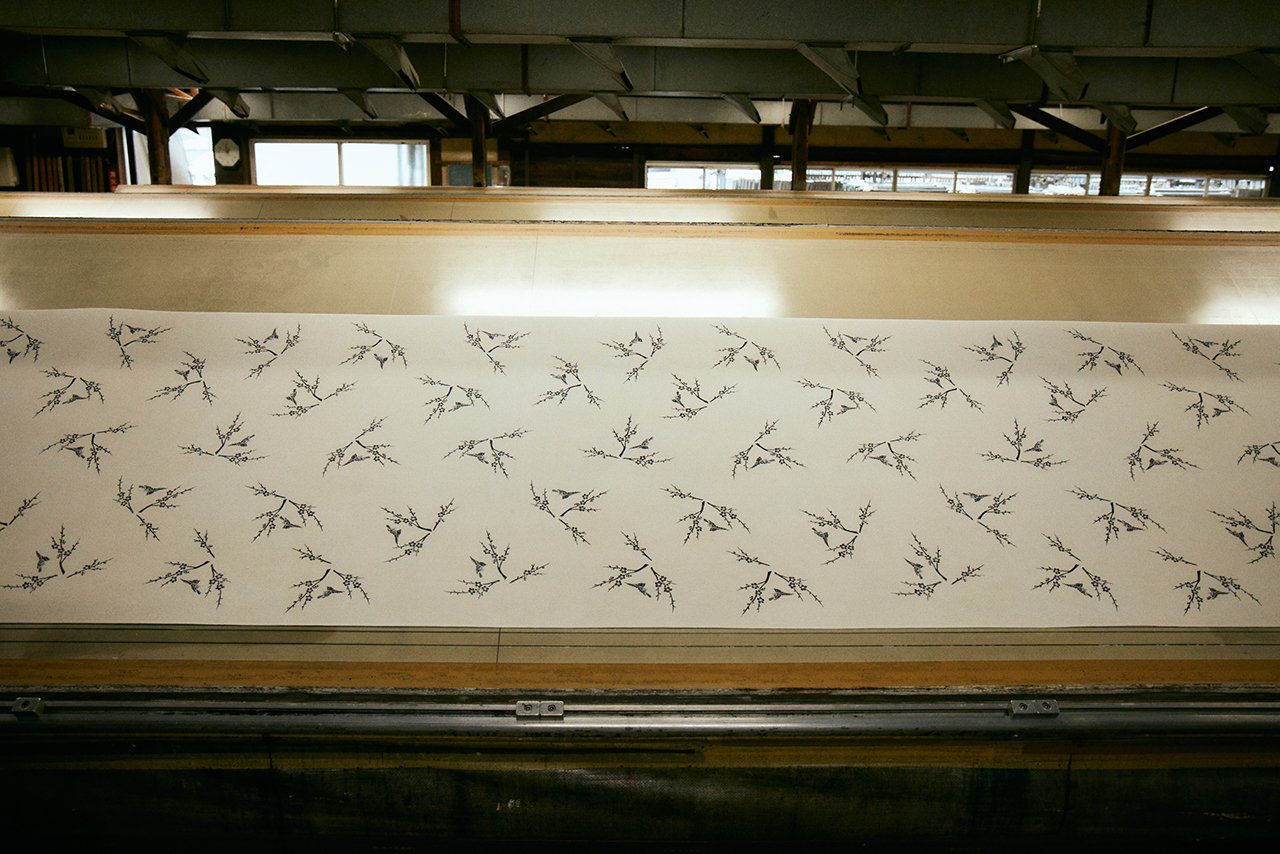

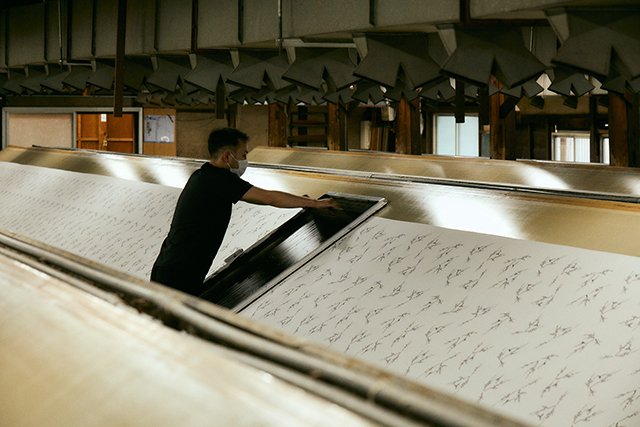

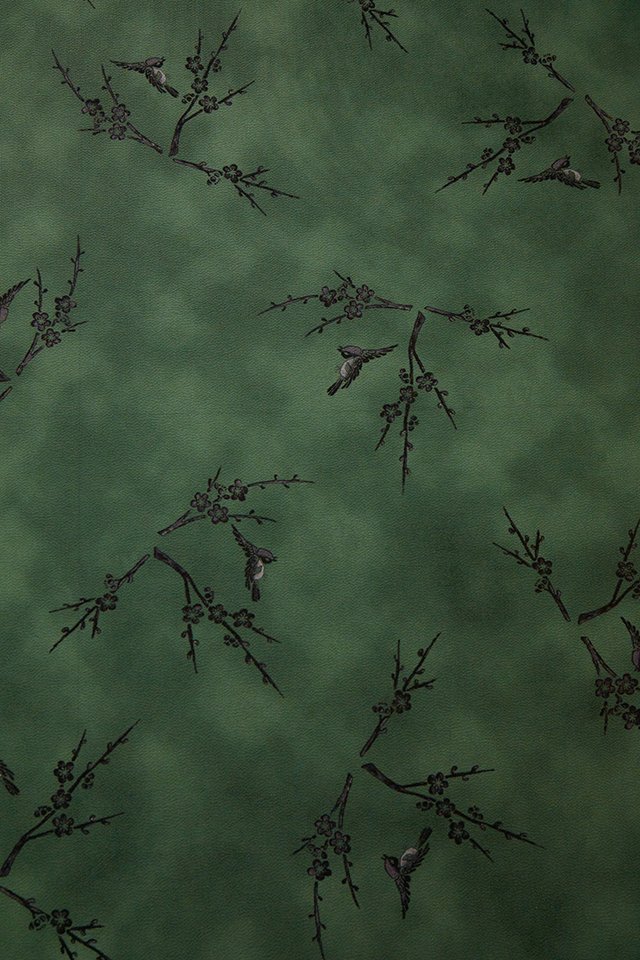

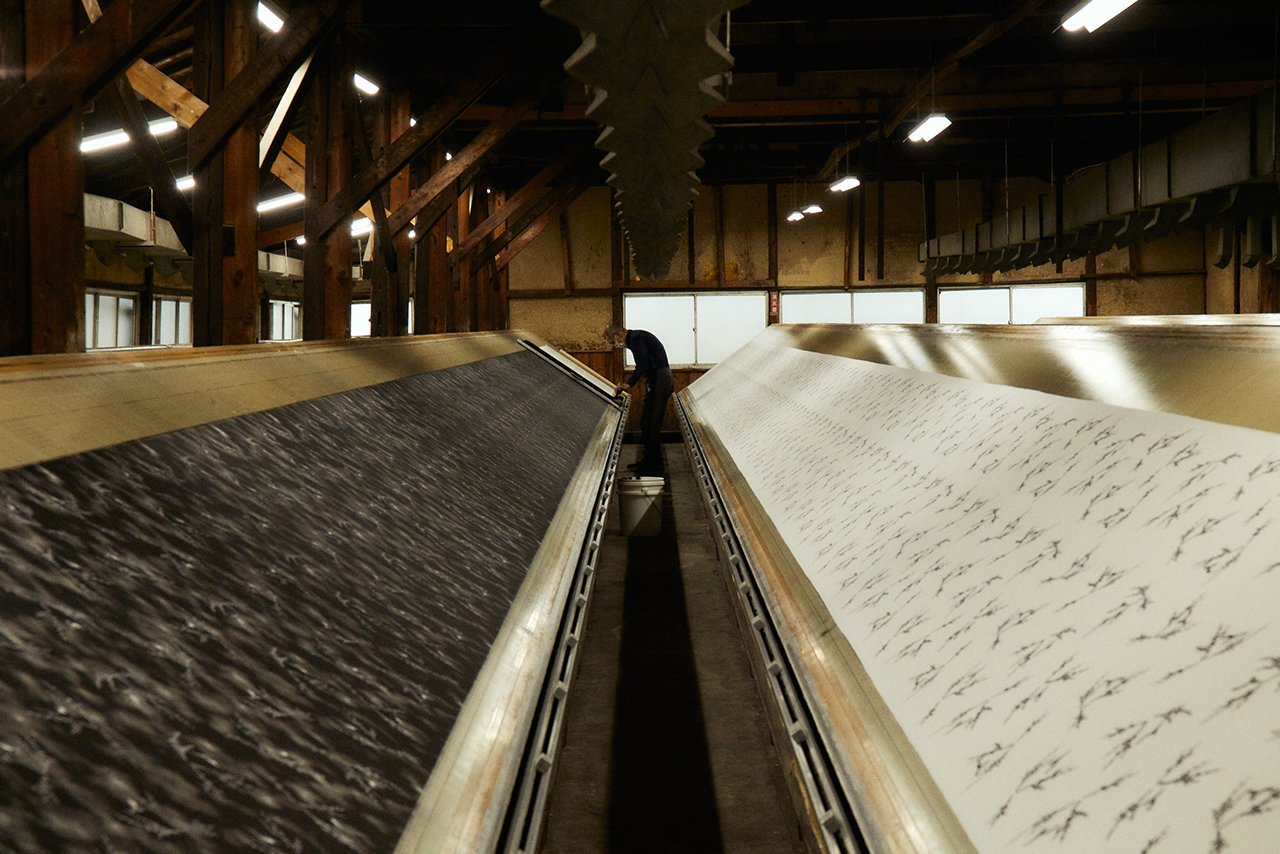

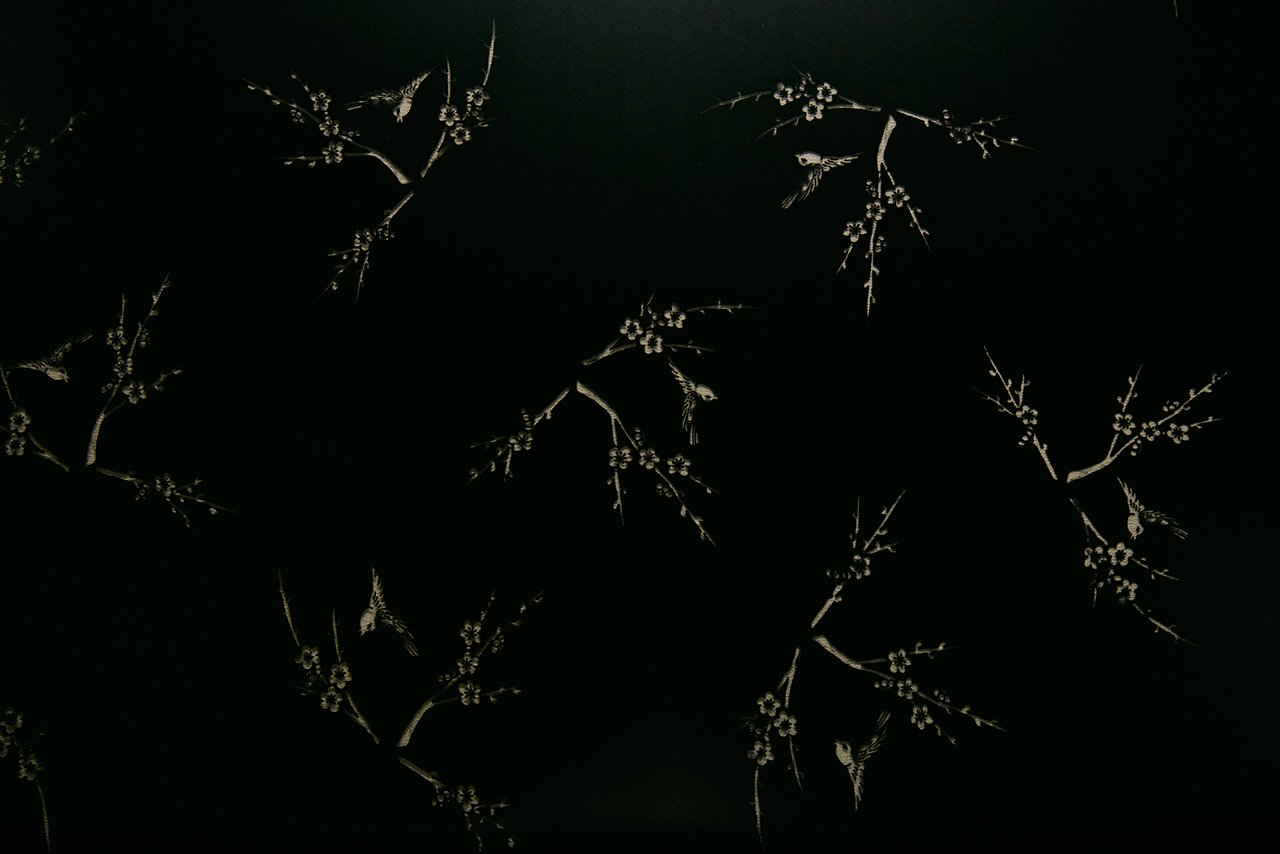

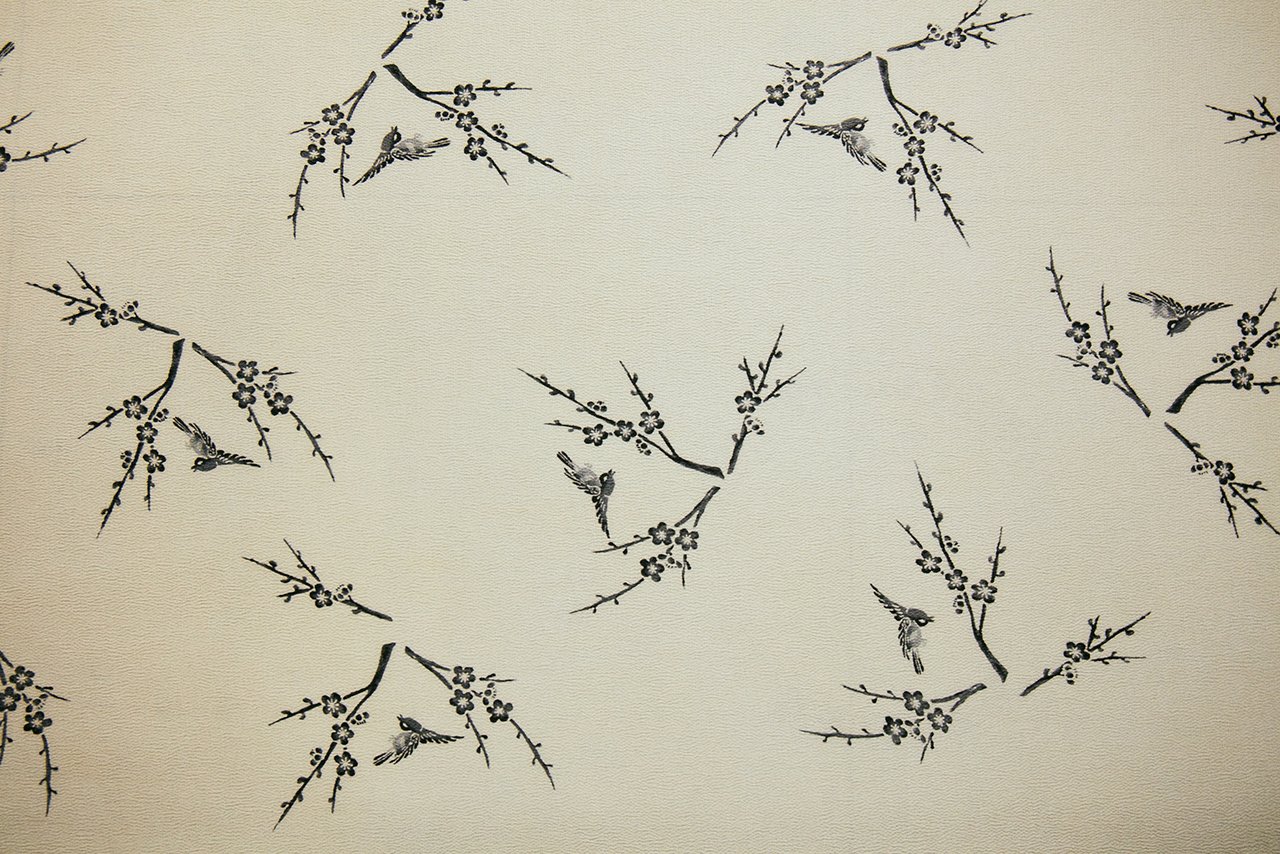

Banba Dyeing oversees the individual dyeing of each Tango chirimen shirt produced by visvim. Founded in 1913 and based in Fushimi-ku, Kyoto, Banba uses the method of te-nassen, a textile printing process where stencils are used to apply each individual color by hand, to dye the shirts. In their workshop, housed inside a traditional Japanese building which has been in use since the Taisho era, there is an approximately 27-meter-long sloped worktop. A fabric adhesive, which is also used for dyeing, is applied thinly over the worktop and about 25 meters worth of fabric--used for furoshiki and the like--is spread over it, while taking skillful precautions not to create any creases. This seemingly simple task requires a level of care only made possible by years of experience.

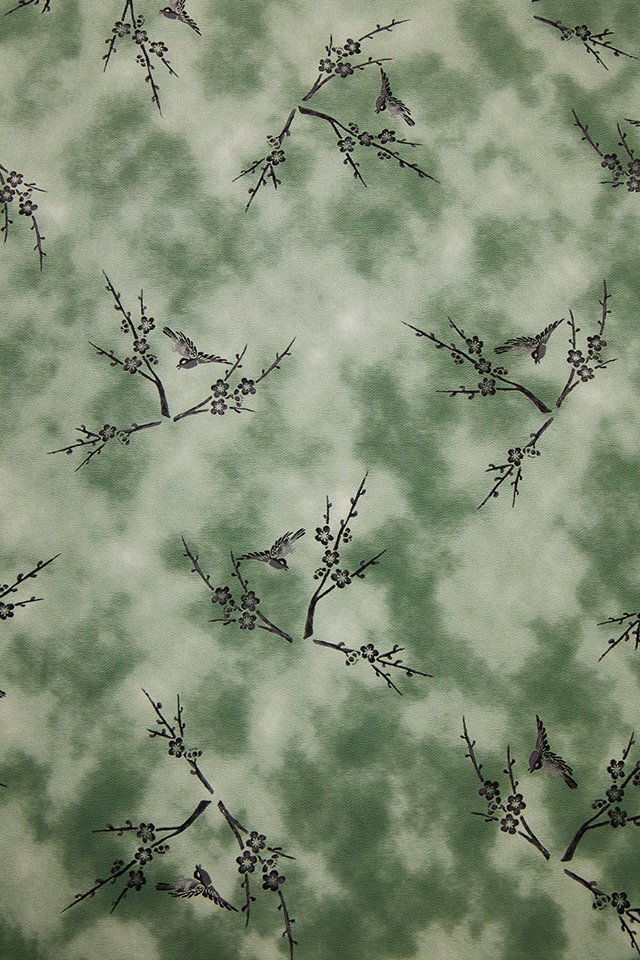

The stencil is then positioned over the fabric, equipment used to hold the adhesive in place are set, then the colored adhesive is poured in, using the process of screen printing a spatula is used to swiftly spread the dye to create patterns one color at a time on the surface of the fabric. Color irregularity can occur if the spatula stops moving during the process, so a single craftsperson dyes an entire 25-meter sheet of fabric in one go. The number of colors decides the number of stencils required, and for this particular visvim shirt, the design itself requires three stencils, and the base color requires two stencils, meaning five stencils are required in total, all dyed one by one to create the finished product.

A particularly difficult part of the process is creating the right color dye. The adhesive, dye, and the auxiliary agent are combined to replicate the color of the reference color sheets. Detailed adjustments are made by the gram to get the right color so all the fabrics being dyed are a uniform color. Aside from the materials, elements such as temperature and humidity affect the color too, requiring a keen eye backed by extensive experience. In the case of silk, as with Tango chirimen, nukanori, an adhesive which resists dye is sometimes used. Nukanori is created by adding salt to a rice bran adhesive agent that is then left setting for around one year prior to use.

To speed up the drying of the fabric, steam is applied as a heat source to a metal plate attached to the worktop from underneath, resulting in sauna-like conditions during the summer months in the workshop. It's a tough job, but the young craftsperson Rei Kojima says, "It's fascinating how the dyeing process completely changes if either the fabric, dye, or tools are changed." Rei once visited the workshop during his days as a student and decided to join the company after being enamored by the dyeing techniques. Today, he supports the workshop alongside the fourth-generation head Kensei Baba, and his predecessor Yoshihisa.

Once the dyeing and drying processes have been completed, the fabric is rolled up, steamed, cleaned with water, then steam ironed. Naturally, depending on the material of the fabric being created, the temperature of the steaming and the way it is cleaned needs to be adjusted. "Silk dyes easily, which in turn makes the process challenging," says Kensei. "Cotton requires very hot water to dye, yet silk dyes at low temperatures. Due to this, if we get the water temperature during the washing process wrong, the color can bleed and spread to undesired areas. Not only this, but there is a huge variance between each silk product. This is because it's a product made from animals--it's a living thing." The final thing the craftspeople rely on is something honed over many years: their instinct. Their steady consistent work conducted every day and their vast knowledge and finely-tuned skills nurtured by their experiences-- all these ingredients are what allow for creation of the final product.

Text: Kosuke Ide

Photo, Movie: Keisuke Fukamizu

Movie edit: cubism